In the series finale of About South, we travel to the E.W. Shell Fisheries Center at Auburn University to discuss a subject near and dear to our hearts -- crayfish. Jim Stoeckel, an Associate Professor at Auburn, and Brian Helms, an Assistant Professor at Troy University, generously share with us their knowledge, expertise, and enthusiasm for this small yet remarkable creature.

The Jewel Mudbug, identified by Mael Glon, Dr. Zac Loughman and Dr. Bronwyn Williams. Read more here.

Residents of the southeastern U.S. are often surprised to learn that this part of the world possesses some of the greatest freshwater biodiversity -- Alabama alone is home to the highest diversity of mussels in the country, raking in 180+ species and counting, not to mention a large array of turtles, fish, snails, and a variety of other invertebrates. But we’re here to talk about crayfish today, and Alabama has somewhere between 80-90 species of them.

Our guests explain the key role crayfish play in freshwater ecosystems, describing them as “omnivores with a capital ‘O.’” They will eat nearly anything, including each other, and everything seems to want to eat them. This places them in a pivotal position within their aquatic systems, where their role changes depending on the species (some crayfish species are more docile, and some, like the ones our host Gina encountered, are quite aggressive). Though the motivation behind some of their behavior remains a mystery, their presence in an ecosystem is vital -- they are important indicators of climate change, pollution, and sediment contamination, and they are an excellent gauge for the health of a freshwater habitats.

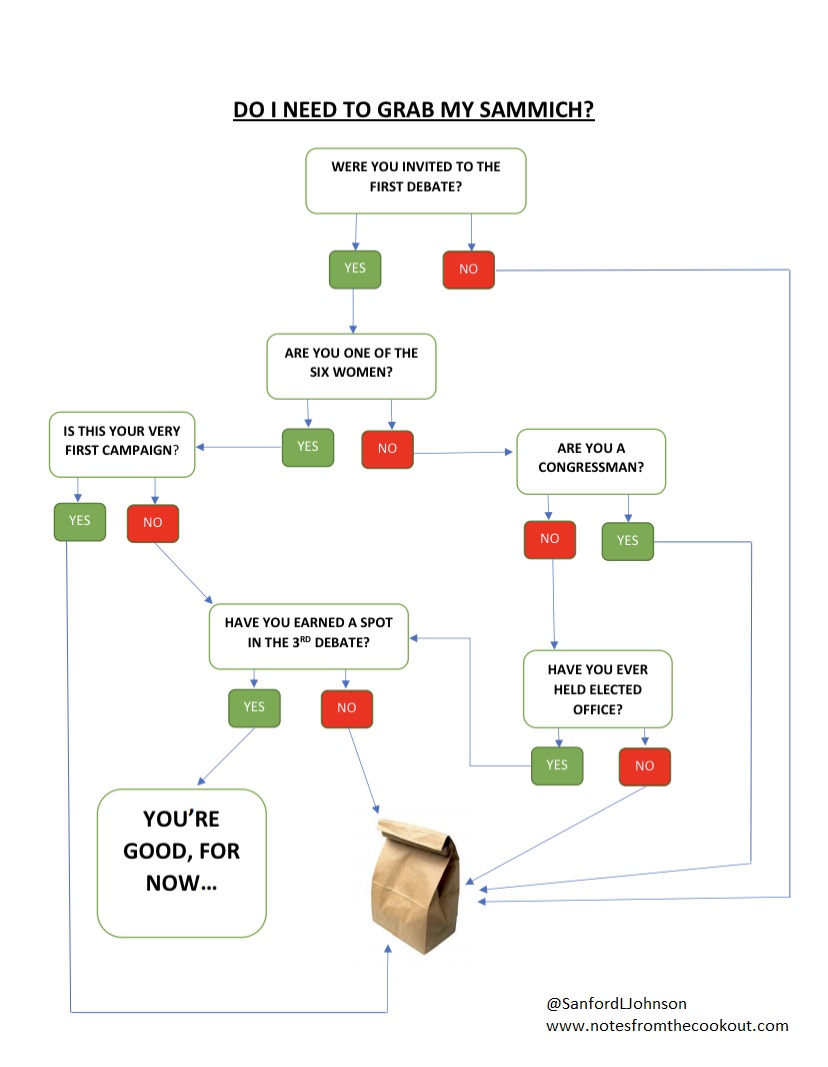

A resin mold of a crayfish burrow. Note: it was nearly five feet tall.

But like most of the country, the southeastern U.S. is rapidly developing its landscape, and on the heels of this change comes the destruction of a beautiful and rare biodiversity. The loss of connectivity between ecosystems presents huge problems for not only crayfish, but all creatures that depend on movement between habitats, and poor agricultural practices threaten fragile species already on the verge of extinction. Brian and Jim emphasise education about conservation, protection, and appreciation for biodiversity to hopefully combat the rapid loss of something so precious to this region. Amazingly, learning about crayfish can do exactly that.

Thank you, Jim and Brian, for helping us bring this podcast full circle. And thank you, listeners, for joining us this season. Stay tuned for the future endeavors of the About South, and until then, take care.